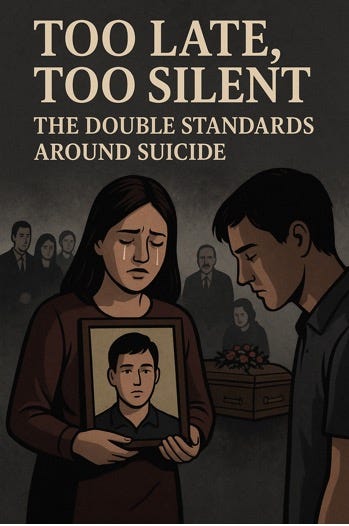

Too Late, Too Silent: The Double Standards Around Suicide

By Punjita Pradhan, MA. Counseling Psychology

There is a tragic irony in how society responds to suicide. When someone dies by their own hand, suddenly, the world takes notice. Tributes are shared, heartfelt words are written, flowers are laid, and a collective mourning begins. Friends and family express regret, remembering the qualities they may have overlooked. The person, who may have felt invisible and unloved in life, becomes the center of attention in death.

Yet, those who survive: family members, close friends, or even individuals who attempt suicide and live face a completely different reality. They are often met with judgment, shame, or silence. Instead of compassion, survivors carry the weight of blame, whispers of guilt, and the heavy pressure of societal expectations. This glaring inconsistency reveals a painful truth: we seem capable of love only when it is too late, and quick to judge when life is still present.

Why People Commit Suicide

Suicide is often misunderstood. It is not a simple desire to die; rather, it is a desperate attempt to escape unbearable emotional pain.

Psychologists describe this as “psychache”, a profound psychological anguish so intense that the person feels there is no other way to survive (Shneidman, 1993). Hopelessness, loneliness, and chronic mental health struggles like depression or trauma deepen the sense of despair. Many who contemplate suicide hide their pain, fearing judgment or misunderstanding.

They may reach out in subtle ways that go unnoticed, or remain silent entirely to avoid burdening others. The societal stigma around sadness and vulnerability compounds this silence, leaving them isolated at the very moment they need care the most.

Research consistently supports psychache as a central driver of suicidal behavior. A study in Frontiers in Psychiatry (2021) describes psychache as “unbearable psychological pain” encompassing feelings like guilt, shame, humiliation, dread, and loss.

Organizations like the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), and the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasize that suicide arises from a complex interplay of unbearable emotional pain, mental health disorders, social isolation, trauma, and stigma.

Their prevention efforts focus on improving access to mental health care, reducing stigma, and fostering supportive environments. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of addressing psychache and enhancing protective factors like meaning in life to prevent suicide.

Love and Understanding That Comes Too Late

After a suicide, society’s response often shifts dramatically. Suddenly, the individual is seen, celebrated, and mourned. Friends and family recall their qualities, apologize for missed signs, and express regret for not doing more. There is a rush to honor the person’s life, yet all of this occurs after they have left.

This delayed recognition is tragic because it emphasizes what should have been present all along: love, understanding, and human connection. Death often becomes the trigger for collective compassion that was withheld in life.

Survivors and the Stigma They Face

Meanwhile, survivors live with a different reality. Families may face direct blame: “Where were you when this happened?” or “Why didn’t you prevent it?” Friends are often silenced, discouraged from discussing the loss, or expected to move on quickly. Those who survive a suicide attempt may encounter judgment, labeled as “weak” or “attention-seeking.”

Cultural and religious norms can intensify this stigma. In many communities, including Nepal, suicide is framed as a moral failing or a dishonor. This forces families and survivors into secrecy and shame, creating further isolation. Rather than receiving care and understanding, survivors are burdened with silence and guilt.

The Double Standards

Herein lies the cruel paradox: society showers love on those who are gone but withholds it from those who are still living. Pain becomes visible only after it is too late; grief is only acknowledged when the survivor is no longer present to feel it.

We write moving obituaries but fail to ask, “How are you really?” We light candles for the dead, yet silence the grieving mother. We celebrate the deceased, but stigmatize the living. This double standard not only deepens the pain of those left behind but also reinforces the silence around mental health struggles, leaving others at risk.

Breaking the Cycle

If we want to prevent suicide and support those affected, we must change the way we respond to pain. Compassion must be present before it is too late. We must normalize conversations about sadness, struggle, and mental health. Families, schools, and communities need to create safe spaces where grief, vulnerability, and distress can be expressed without fear of judgment.

Showing love, offering understanding, and simply listening can save lives. It is our responsibility to recognize the humanity in those who suffer, both the living and those affected by loss. Only then can we dismantle the cruel double standard and foster a culture of empathy.

Conclusion

Suicide is not just a personal tragedy; it is a societal mirror, reflecting our inability to recognize pain while life is present and our tendency to judge those who survive. Every life lost, every survivor silenced, is a reminder that we must act differently: to offer care, presence, and understanding today, not tomorrow.

"We must stop waiting for death to teach us how to love. The true prevention of suicide begins when we learn to honor people’s pain, stand beside survivors without judgment, and choose compassion while life is still present."

Bridging Compassion: A Cross-Cultural Webinar on Suicide Prevention (Nepal & Sri Lanka)

Date: September 10, 2025 (World Suicide Prevention Day)

Time: 6:00 PM – 7:30 PM NST (5:45 PM – 7:15 PM SLST)

Platform: Zoom – Join Here

Meeting ID: 979 6690 7748 | Passcode: 774646This webinar brings together experts from Nepal and Sri Lanka to share culturally sensitive strategies for suicide prevention, reduce stigma, and foster hope across borders.

References

Shneidman, E. S. (1993). Suicide as Psychache: A Clinical Approach to Self-Destructive Behavior.

Frontiers in Psychiatry. (2021). Psychache and Suicidal Behavior.

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Suicide Prevention.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). Understanding Suicide.

World Health Organization (WHO). Suicide Worldwide in 2021.